Nowt, nada, zilch: there is nothing new about nothingness. But the moment that the absence of stuff became zero, a number in its own right, is regarded as one of the greatest breakthroughs in the history of mathematics.

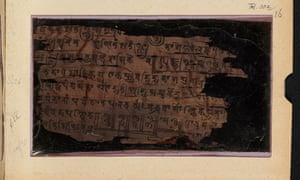

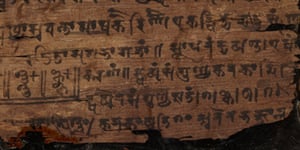

Now scientists have traced the origins of this conceptual leap to an ancient Indian text, known as the Bakhshali manuscript – a text which has been housed in the UK since 1902.

Radiocarbon dating reveals the fragmentary text, which is inscribed on 70 pieces of birch bark and contains hundreds of zeroes, dates to as early as the 3rd or 4th century – about 500 years older than scholars previously believed. This makes it the world’s oldest recorded origin of the zero symbol that we use today.

Marcus du Sautoy, professor of mathematics at the University of Oxford, said: “Today we take it for granted that the concept of zero is used across the globe and our whole digital world is based on nothing or something. But there was a moment when there wasn’t this number.”

The Bakhshali manuscript was found in 1881, buried in a field in a village called Bakhshali, near Peshawar, in what is now a region of Pakistan. It was discovered by a local farmer and later acquired by the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Translations of the text, which is written in a form of Sanskrit, suggest it was a form of training manual for merchants trading across the Silk Road, and it includes practical arithmetic exercises and something approaching algebra. “There’s a lot of ‘If someone buys this and sells this how much have they got left?’” said Du Sautoy.

In the fragile document, zero does not yet feature as a number in its own right, but as a placeholder in a number system, just as the “0” in “101” indicates no tens. It features a problem to which the answer is zero, but here the answer is left blank.

Several ancient cultures independently came up with similar placeholder symbols. The Babylonians used a double wedge for nothing as part of cuneiform symbols dating back 5,000 years, while the Mayans used a shell to denote absence in their complex calendar system.

However the dot symbol in the Bakhshali script is the one that ultimately evolved into the hollow-centred version of the symbol that we use today. It also sowed the seed for zero as a number, which is first described in a text called Brahmasphutasiddhanta, written by the Indian astronomer and mathematician Brahmagupta in 628AD.

“This becomes the birth of the concept of zero in it’s own right and this is a total revolution that happens out of India,” said Du Sautoy.

The development of zero as a mathematical concept may have been inspired by the region’s long philosophical tradition of contemplating the void and may explain why the concept took so long to catch on in Europe, which lacked the same cultural reference points.

“This is coming out of a culture that is quite happy to conceive of the void, to conceive of the infinite,” said Du Sautoy. “That is exciting to recognise, that culture is important in making big mathematical breakthroughs.”

Despite developing sophisticated maths and geometry, the ancient Greeks had no symbol for zero, for instance, showing that while the concept zero may now feel familiar, it is not an obvious one.

“The Europeans, even when it was introduced to them, were like ‘Why would we need a number for nothing?’” said Du Sautoy. “It’s a very abstract leap.”

In the latest study, three samples were extracted from the manuscript and analysed at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit. The results revealed that the three samples tested date from three different centuries, one from 224-383 AD, another from 680-779 AD and another from 885-993 AD, raising further questions about how the manuscript came to be packaged together as a single document.

The development of zero in mathematics underpins an incredible range of further work, including the notion of infinity, the modern notion of the vacuum in quantum physics, and some of the deepest questions in cosmology of how the Universe arose – and how it might disappear from existence in some unimaginable future scenario.

Richard Ovenden, head of the Bodleian Library, said the results highlight a Western bias that has often seen the contributions of South Asian scholars being overlooked. “These surprising research results testify to the subcontinent’s rich and longstanding scientific tradition,” he said.

The manuscript will be on public display on 4 October, as part of a major exhibition, Illuminating India: 5000 Years of Science and Innovation, at the Science Museum in London.

ESSAYS ON GAME DESIGN: To Hell With Balance

Sep 9

Posted by occu77

ESSAYS ON GAME DESIGN

Essay Two: To Hell With Balance

I’m gonna say something that might shock some of you guys. Then again, maybe not.

Balance, go to the Devil, and burn in hell. And while there sip septic tea with him til you’re really needed again. And chances are it won’t be often. But whatever the case, don’t call me, I’ll call you.

I’m working on a fantasy Role Playing Game, I’m not designing an algorithm, doing covalence equations, or writing a computer program to calculate a moonshot at apogee.

So sometimes in-game my players get their noses busted and spleens ruptured by a dragon that in real life they couldn’t ever easily kill. Not with bow-sticks and knives and harsh words anyways. Good, it’ll teach em a lesson about danger and risk and what it actually costs people.

And sometimes they’ll whip out their Horn of Resounding and bring down the walls of Jericho, or slay a few giants with the Jawbone of an ass. Good, sometimes you catch a miracle in midair, deserved or undeserved. Sometimes you get the bear, and sometimes he gets you. That’s life.

But in any case, as far as the game goes, the player is fascinated, interested, intrigued, involved, worried, anxious, and maybe even occasionally excited again. Perhaps shocked and ecstatic from time to time too, just to boot.

Balance, he ain’t my god. I don’t owe him any real sacrifices. He’s more like the grey-skinned Graeæ sisters than bright Apollo. Only one eye to see with, a lot of double talk, the bite of a one-toothed wonder – and in the end, disaster, not glory. You can’t trust Balance to point the way to the future, cause he’s more consumed with his own reflection in the mirror than with anything remotely heroic happening. Static, stale, sterile, sluggish, and simple-minded. A dotard of dullness. No poetry of soul, just an arrested arithmetic of tedium. More Echo and Narcissus, more Sound and Fury, than Thunder and Lightning.

I liked the original version of D&D. I like the 4th Edition, at least many things about it. But I see now that this pernicious idea of “balance” that crept in like the Serpent at Eve in Paradise, balance as an end in itself, especially in a fantasy game of all things, is more assassins’ poison than golden Ambrosia. If I have to kill wonder and potential just to achieve balance, then I have to kill fantasy just to achieve boredom. Thank you modern RPG Fantasy Game Theory of Balance, but I think you’d be happier working as a stock-boy in the warehouse of modern mediocrity, than a gate-keeper to the temples at Mount Olympus.

So Balance, my fine feathered fowl of gutless acquittal, go to hell and burn awhile. Maybe you’ll cook into a decent potpie.

Invention is as invention does. So, I’m gonna start designing fantasy games and adventures again, even D&D ones, where magic happens, miracles save the day, monsters are dangerous and feral, the voice of God rumbles across the sky, kingdoms topple, heroes struggle, players say, “Now that’s what I’m talking ‘bout!” and imaginations catch fire.

Balance can burn in his own oven… and stew in his own juices.

Share this:

Posted in Adventure/Adventure Development, Commentary, DESIGN OF THINGS TO COME, Dungeon Master/Game Master, Essay, Game Design, Gaming, MY WRITINGS AND WORK, Uncategorized

2 Comments

Tags: role playing